Rev Arthur Henry Evans

1880 – 1948

Arthur Henry Evans, son of Rev William Jones Evans and his wife Eliza, was born in Gloucestershire. After gaining a BA at London University, he attended Wells Theological College and was ordained as a Church of England minister in 1905. Arthur married Olive Frances Rogers Younger in 1917 with two sons (John and Paul) following in 1918 and 1922.

In 1930 Rev Evans was instituted to the living of Buckland Filleigh (as Rector) by the Bishop of Crediton, and two years’ later was presented the Vicarage of Shebbear by the Lord Chancellor.

As well as parish duties he was active in community affairs, and a well-liked speaker for festival occasions at local churches. Rev and Mrs Evans stayed in Shebbear until 1946 when he took the living at Wotton Underwood, near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. He passed away in 1948.

Bio written by Bridget Deane

Below is the transcription of Rev Evan’s booklet about his observations on Shebbear immediately after WW2.

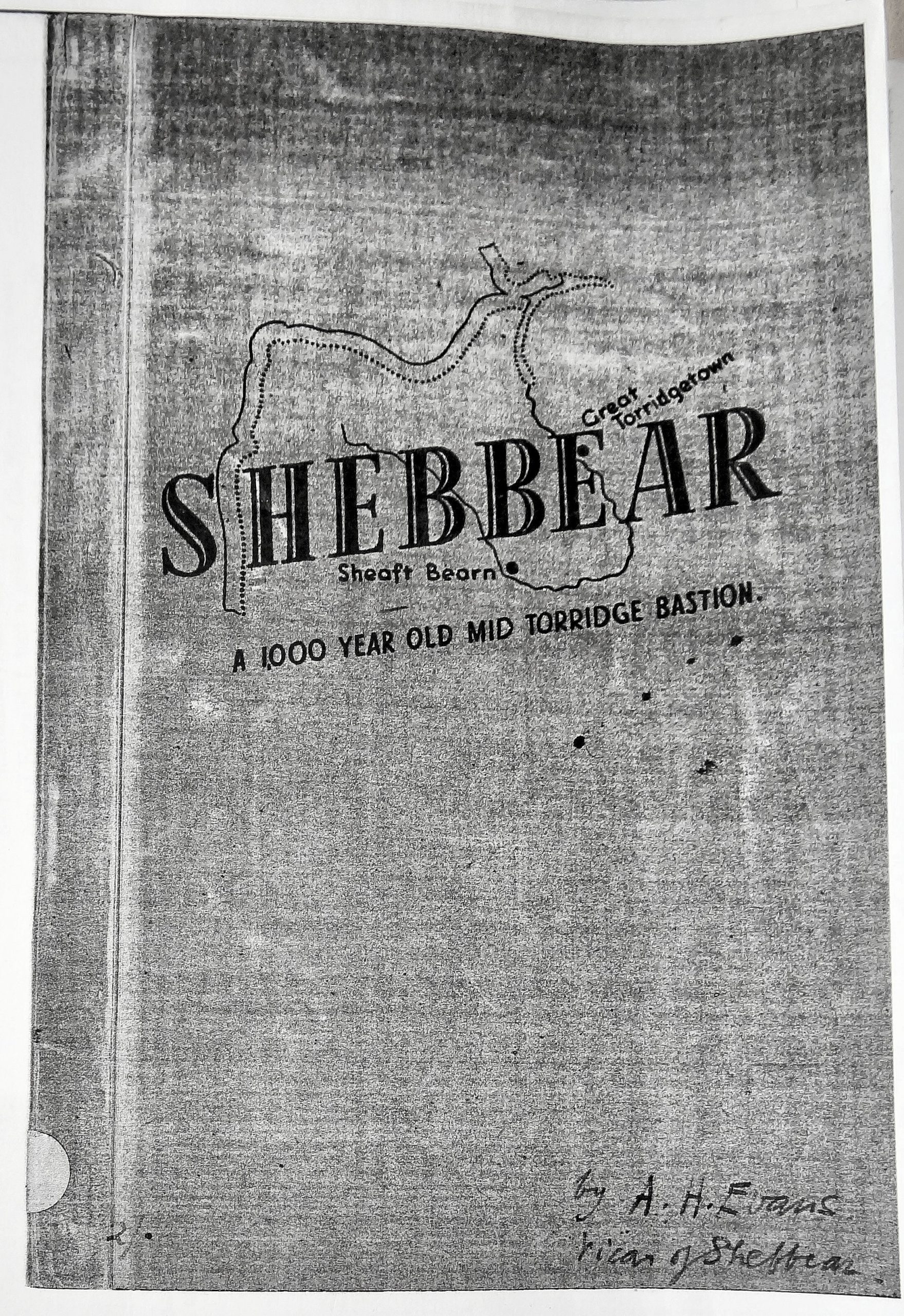

SHEBBEAR

A 1,000 YEAR OLD MID TORRIDGE BASTION

By A H EVANS

Vicar of Shebbear

Historical.

MANY of the valuable records of Devon parishes no doubt perished through the destruction of the Public Library at Exeter in the savage air attacks of May,

1942. Among them probably precious records of the mid-Torridge Village of Shebbear. This is a pity. Most villages have in their history some pages at least that are worthy of note, and Shebbear would be high upon the list.

There are at least seven different spellings of the name. In 1050 it appears as Sceaft Beara. Domesday Book calls it Sepesberia. At one time the name seems to have been Shaftesbury, for Edward Plantagenet, Earl of Kent, son of Edward I, had a grant of the Manor of Shaftesbury, and Dugdale’s Baronage says ” It was the Devonshire and not the Dorsetshire Shaftesbury that was meant.” One feature of all the spellings is the final vowel, a, e, or y, which now for some reason has been dropped. There is no settled meaning of the name either. The connection with sheep seems an obvious one, but some see a reference to the rich woods of oak, ash and beech, and to the handles or shafts they would furnish, for business or for battle. Bear or bearu is the common Scandinavian word for a wood or copse.

Shebbear was of sufficient importance in Saxon days to give its name to a ” Hundred,” a group of one hundred villages or hamlets for administrative purposes. Both Bideford and Lundy Isle were once included in the Shebbear

Hundred. The Hundred Moot, or Meeting, was first at Merton, in the South-East of the Hundred, but it was later transferred to Shebbear in the South-West.

And Shebbear Manor was a: Royal Manor, held for a time by Earl Harold ” the last of the Saxons,” Godwin’s son. After the Battle of Hastings, Baldwin de Redvers, a cousin of William the Conqueror and one of his captains in the battle, was made Earl of Devon and received 181 manors in the county, among them, that of Shebbear. It was this same Baldwin who built Okehampton Castle, to guard the highroad into Cornwall and North Devon; and Exeter Castle, too. Shebbeare is mentioned in the particulars of a subsidy granted for a Crusade, in 1274.

Later the Manor of Shebbear came into the hands of Sir Ralph Neville. Earl Of Westmoreland. In 1570 the then Earl of Westmoreland was “attainted ” by Queen Elizabeth for aiding Mary, Queen Of Scots, and all his lands became forfeit to the Crown. It is probable that after this, much of the Shebbear Manor was sold to the local gentry. or to the tenants in possession. At the beginning of the 19th century the Fortescues were Lords of the Manor. From them it passed to the Kingdon family, who had considerable estates in North Cornwall and North Devon, and when in 1854 Paul Augustine Kingdon. a London barrister, married Parson Peter Davy Foulkes’ daughter, Elizabeth Fortescue Foulkes (one of a family of 14 at the Vicarage), there began that close connection between the Kingdon family and Shebbear that has continued ever since.

There were. at one time or another, several estates of importance in the village. Ladford belonged in the 15th to John, son of Sir William Hankford, Chief Justice of England, who is supposed to have built Bulkworthy Church Sir William, accidentally shot by his servant. lies buried at Monkleigh Church, in the Annery Chapel. Ladford was of such importance that in 1406 licence was granted for the building of a private chapel there. The remains of this chapel are said to have been used in building the Rectory of Newton St. Petrock. In the church there is an effigy of a Lady known as the Lady of Ladford, apparently the Lady Bountiful of the place. Another private chapel was built at Alvecott (Allacott?) and dedicated to St. Stephen, December 4th, 1409.

There is record of an estate of considerable importance rolled Spraywood. This belonged in 1811 to the Rev. William Holland Coham, and adjoined some lands he owned in Black Torrington. Coham Bridge was one of the results of this joining of the estates,

As interesting an estate as any is Lovacott. In Domesday Book an entry listing the property of one Ruald Adobed, states—” Ruald himself holds Lovacott. Lofe used to hold it in King Edward’s time, 1045, and paid tax on half a virgate (15 acres ?). The arable land consists of 2 carucates (?). There are two villeins and twelve acres of pasture. Formerly worth 30 pence, now 50.” This is one of the most complete early accounts of a Shebbear

estate, and doubly interesting as giving the name both of the holder at the Domesday Survey, and also of the Saxon Franklin or freeholder, who gave the place its name.

There are Holroyd and Libbear, too, that look as if, in earlier times, they might have played no mean part in the life of the place.

But it. has been one of Shebbear’s misfortunes that no Lord of the Manor has ever settled in the place, and expressed in close personal contact. the attachment that many must. have felt for this Old Mid Torridge outpost. And, unless the present revival of agriculture is going to be permanent the days of resident Lords of the Manor are probably gone for ever.

The Place and the People.

EARLIER than history comes geography. Places and people are what land formations and climate make them. An aerial view of Shebbear would show it standing guard at Dipper and Gidcot, two of the central river gates of what may be called the ” Torridge Salient.”

For most. people Devon means South Devon, the warm, narrow, sheltered corridor from Axminster to Plymouth, with the main Exeter to Plymouth road and railway as inner boundary, and Dartmoor the dark mysterious background. But Devon is very much more than this. It has great varieties of climate and of scenery. Red Devon by the Southern Sea balances Grey Devon by the on the north. The warm, indolent suns of Torquay contrast with the keen breezy sunshine of Ilfracombe ; the dark northern slopes of Dartmoor with the sunny southern slopes of Exmoor.

But there is a Devon of which few people know—the Torridge Salient, Celtic Corner, the 25 miles long strip carved out by the deep cut Torridge gorge. Few rivers pursue a straight and even course from start to finish, but fewer still turn right back upon themselves as does the Torridge, and empty their waters into the sea a few miles only from where they take their rise.

Of this encircled region of and woodland. Shebbear is a natural centre. It is a typical village Of the Salient, always intensely conscious of the river and of all that it has meant. Over it would come the traders bringing their wares from the outside world. Over it, too, might come invading hordes. The river gave Shebbear folk their food, it watered their fields and flocks and herds, and it gave the'” a solid barrier of defence.

In winter the river rises rapidly in its narrow channel and for days together all the fords and smaller bridges are impassable. ” The waters are out,” the people will say, and then the only way of getting across to the mainland is by one or other of the large modern bridges—Hele Bridge. near Hatherleigh, or Woodford Bridge, near Holsworthy. There is little doubt that this region, cut off so sharply by Nature. is one of the remote Western fastnesses, against which the storms of foreign invasion raged in vain. Here the Celt maintained his hold throughout the centuries.

There are no Roman remains in Shebbear, but barrows. burial places of the old native people, arc common features of the district. Near Stibb Cross a massive earthwork, Durpley Castle. with ditch and outer rampart, provides one of Shebbear’s few antiquities. The cone-shaped hill is easily approachable on the West side, but it falls away steeply elsewhere. and must have commanded a wide view of the parts from which invasion always threatened. At the summit is a circular excavation, nearly 30 feet in diameter, and some 20 feet in depth. This may have been one of those underground storage places, where the old Celts used to hide their grain against emergencies.

Dotted all along the river valley are the ford or bridge heads in pairs, the one over against the other. East Putford faces West Putford. Shebbear, guarding the two crossings, at Gidcot and at Dipper, stands over against Bradford ; Sheepwash on its precipitous hill, looks across at Black Torrington ; Merton keeps watch on Dolton. All of them peaceful and unguarded now, but in the old days strongly sentinelled and stockaded.

Shebbear must have been a much bigger place in the past. The oldest inhabitant. Richard Blight, 95, says he mind at least 40 houses, standing and occupied, that now completely vanished. “Vanished” because North

Devon cottages do not continue standing as picturesque ruins. The walls being mostly of “cob.” a primitive composition of clay and straw, rapidly disintegrate when once they are left unroofed. Forty houses. each with a family of the old Village size would make easily possible the population figures given for earlier days, 1,006 in 1801, 1,109 in 1861.

An agricultural community in the main. but it would always have been something of a market centre, too. People talk of going to “Shebbear town.” The townsman thinks of shops and pavements and lights. But the local people are right. The ” tun ” or town, in old days, was merely the fortified centre of the village. where the headdon or headman lived, and things needed on the farms could be got.

The life and interests of the old village are reflected in the prevailing names. In a village settlement, bounded by the river, and owing to the river much of its safety from attack. the Bridgman was always likely to a person of importance. Ackland is another name connected with the land. Most of us remember King John’s nick-name, Lackland. He was the ne’er do well of the Royal family, who could never be trusted to keep for long any land entrusted to him. The name Ackland is well known in Devon and the family is spread in all directions and through all varieties of social grade, some landed proprietors, others landless workers, much after the fashion of the royal name of Stuart. The name may have originated in some such way, and now remains the common heritage of all Acklands, whether they have land or not.

Quance, or Squance, is a less frequent name. Lovers of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream will be reminded of a genuine old English country friend, Peter Quince, surely an early relative of this good Devon family.

The Petts are another widespread and important group; possibly, as they claim, of French descent. Old John Thorne Pett, the head of the family, declares that 4O good fighting men would answer to the call if the fiery cross went round.

Mill and Milman. again, suggest a time when stone grinding and home milling were living interests and industries and when the water wheels at Ladford, at Dipper, at Backway and at Gidcott were centres of clattering, rumbling activity from dawn to dusk.

The river influences the village in many ways. Each of the farms that borders on it has its own stretch of fishing. excellent salmon and trout. Old Bishop William Cecil used to say that if as much pains were taken to develop the Torridge fishing as is taken on other rivers, it would become as well known and as much sought after as the fishing in any other river of equal size in the British Isles.

But the heart of the village life is the good earth. The ground is generally too wet for wheat, but oats do well. and barley and potatoes; and the apple orchards yield abundant fruit, mostly apples for cider making in the great factories of South Devon. There is fine pasture land carrying stock of first rate quality, and dairy herds that produce the Devon milk, cream and butter known all the world over.

A vivider picture of the people and their ways of thought and life may be gained from a story than from reams of writing or description. They might not admit it, but deep down in the subconscious, it may be that the prime preoccupations of the people are the Lord and the land. Shebbear people love their gardens and their fields. Their whole being centres round them; tilling and harvesting. auctioning and marketing are life’s unchanging occupations and the never threadbare subject of conversation from day to day.

Next to their gardens and their fields, they love preachers, preaching. and the Word. When a noted evangelist comes, there go out unto him all Shebbear and all the region round about, and they of Holsworthy and of Torrington. not always, if must he admitted. confessing their sins,” as in the days of John Baptist, but always wrapt in the mystery and magic of the Word. At one of his visits to Shebbear, Gipsy Smith. noting that the field surrounding the marquee that had been put up for his evangelistic meetings was packed with cars, remarked that the local farmers were reported to be going to the dogs, but as far as he could see. they were going very comfortably in their cars.

In towns the man who can make good after-dinner speech is in constant requisition. In North Devon there is always room for the man of the Word. Whether parson, minister, or lay evangelist, the preacher seldom lacks a welcome at any gathering and on any occasion, missions,

revivals, anniversaries, weddings and most of all funerals. for the Celt as H. V. Morton notes “has a genius for the glorification of sorrow.”

The preacher takes the place of the bard in more primitive communities. The people look to him to clarify their thoughts and to give expression to their deep inarticulate ponderings about the Lord and the land. People in the busy towns may well long, on Sundays, for the silences of sabbath worship, but country people who spend their whole lives in silence on the land, tend to seek release, on Sundays, in the clamant ministries of the word.

Some stories. then. Dr. Blatchford vouches for their truth. And first of all a garden story, the carrot story. At the flower show first prize went to some marvellous looking carrots from a Shebbear garden. An aged Black Torrington native, who had been a famous gardener in his day, be examining exhibits and looking them all over. holding them close up to his spectacles and peering into them at range. He soon satisfied himself that these particular prize carrots had been deftly doctored, and their imperfections made good with the aid of carbolic soap. ” Aah!” he snorted. with profoundest scorn, as he put them down on the Show table again, “there be a purty zet of rogues down to Black Torrington, us did always zay, but these yer Zhebbear volk do bate ’em all.”

Stories of preachers and preaching are plentiful. One year there had been, most unusually for North Devon. a very dry early summer, and in a small local chapel the minister offered prayer for rain. The rain came, and having once come, it kept on. and as harvest time approached, it became deluge. The minister who had asked for the rain decided that he would have to do something about it. So he took up his parable the pulpit and said- “O Lord, when us did pray for rain, Thou knowest us did mane those dappity little zhowers, but do ‘ee look now, Lord, this yer’s fair ridiklus.”

On another the service was being taken by a lay preacher who had made some efforts to cultivate a theatrical style, the better to impress his hearers. The subject was return of the Prodigal Son, a fine field for effect. With deepening emotion much pointing of fingers and waving of arms, he to describe the

Wanderer’s homecoming— “And then ‘er cooms hoam to varm. There a cooms. down the road—doan’t ‘ee zee un, with his clothes all rippit to raggets, and plaistered all over with a proper mess of pig’s dung.”

Close to Nature. true enough to the land. Nowhere better than here will you catch the ring of the good old Devon dialect. Not often will you find prettier children, or breathe a richer air. choice blend of country, sea and moorland, than in the Torridge Salient—Celtic Corner.

Shebbear Stone of Destiny

ONE, of the first things the visitor notices. as he enters the village Square at Shebbear. is the old oak tree, at the foot of which lies the Shebbear Stone, of which so much has been said and written.

The stone. which weighs a ton or more. is a rough, flattened oval in shape. reddish in colour, and of some archaic igneous formation; certainly not, a local stone. If any of the lce Ages had ever penetrated so far south. scientists might have called it an “erratic.” Popular superstition. ever ready to link up Satan with the strange and mysterious, calls it a Devil’s Stone. All that the oldest inhabitants can say is that, so far as living memory goes. the stone always turned over each year, on the night of November 5th. Men of village assemble after dark. and when all is ready, the ringers among them go to the belfry and ring a first warning peal. They then return to the Square. where an interested company of onlookers has usually gathered. By the light of lanterns and torches great stone is heaved up, and solemnly turned over. Then follows more ringing of the bells, and after further talk. the business of the day is ended, and Shebbear’s peace and prosperity assured for another twelve months..

There seems little doubt that the ceremony has a religious origin. A recent writer in Hastings’ Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics says—” Given an ancient dedication to St. Michael and All Angels. and a site associated with a headland, hill top, or spring, on a road of early origin, it is reasonable to look for a pre-Christian sanctuary, a prehistoric centre or religious worship.” These conditions are almost exactly fulfilled at Shebbear.

It was a fundamental aim of the early Church. and definitely formulated by Pope Gregory in his instructions to the missionaries he to these islands, that religious observance should not be destroyed. but, wherever possible, turned to Christian purposes.

The date, November 5th is curious. Quite certainly the stone, and almost certainly the custom of turning, go back far beyond Guy Fawkes’ Day. The position of the stone. due East of the Church. and due south of the oak, has led some to infer a connection with sun-worship. which it thought the November 5th bonfires would emphasise. Some have gone further and discovered an association with worship of Baal, and the old Phoenicians, whose trading for tin centred in Cornwall and Devon.

In 1933. at. the corning of a new Vicar. November 5th that year falling on a Sunday, the congregation at the Church were asked, after the Evening Service. to gather round the old stone and invoke the blessing of Almighty God on the village and on whatever there might he of good in what the old stone stood for, ” sanctifying it with the word of God and with prayer.” Later the some evening the usual turning of the stone look place. A sequel to this was a notice found affixed shortly after to the stone. recording strong protest at a Christian service having been held over a heathen stone.

There matter rested, and the turning of the stone went on with alternating waves of public attention and neglect, until 1939, when the war black-out regulations made the carrying out of the time-honoured ceremonies impossible. November 5th went by unmarked that year, but there seems to have been a feeling that the safety and well-being of the village were being jeopardised by the neglect, so the turning of the stone was carried out a few days later, under war-time austerity conditions. It is possible that some. of the villagers saw in the grim events of 1940 a justification of popular superstitions regarding the stone. Be that as it may, there have been no further omissions or delays in the stone turning, and it is likely that the first November 5th after peace has been declared will be a colourful occasion in Shebbear Town.

The Village Square and the Parish Church.

There are seven chief buildings facing on the Village Square at Shebbear. They are typical not only of a Torridge village, but of English villages generally. It is the English Church’s plan for a village.

There is Parish Church, where the parish folk meet for prayer and praise and worship, where the bells peal out in celebration of every great event in the life of village or of nation; where young men and maidens marry and are given in marriage; where there are baptized, and where the passing generations sleep in peace, their quarrels all forgotten.

There is the Village Inn, once the Church House, and bearing cut into its wall, the initials of the two churchwardens of day. Not a mere drinking house, as inns so often have tended to become, but a wholesome place of meeting and refreshment for all and sundry, and a place of rest and lodging for visitors and passers-by.

There is the Post Office, in front of which drew up in old days the slow-moving, horse-drawn mail cart, now smart and speedy van of bright Post Office red.

There is the Village Shop. the general stores, with its over door, where everyone turns in to buy what they need of food and clothing and household goods, and to pass the time of day.

There is the doctor’s house. Who more important in the village community than the country doctor, the friend and comforter of all alike.

And there is the village school, built by Peter Davy Foulkes, the Vicar, for until the middle of the last century the only school on Shebbear was that provided by the Church and carried on in the little old building that is now the church room. Great. battles were waged Iater on as to the ownership of this room; the door was lifted off and carried away, the parson tipped over on the floor, and such fierce Ianguage used on both sides that, the whole Square might have seemed to on the verge of fiery dissolution. In the end the rulings of the Charity

Commissioners had to be sought, and a solemn assembly of local worthies and bewigged counsellors to settle the fate of this poor little old room. The judge ruled that ” it be and remain Church property . . . all who hold otherwise to be reckoned and deemed contumacious persons. liable to the high displeasure of our Sovereign Lady, Queen Victoria.” Many of the old inhabitants can remember their schooling days there. They can call to mind clambering up the wide open chimney of the old schoolroom fireplace, and exploring the hollow bowels of the old village Oak tree just outside the door.

And there, under the very shadow of the church is the farm house, backed by its yards and ricks and linhays, its fields stretching away down the hill to Pitt Water, which hurries along its rocky course, to join Old Father Torridge in the vale.

Once there was a forge and smithy in the Square. almost the most characteristic of village buildings, and then the whole sweet blessed round of English country life found outlet and opening on this Old Torridge village square.

The Church of St. Michael and All Angels stands at the Western end of the Village Square. It occupies in all probability the site of an earlier Christian Church, possibly the site of a Celtic shrine of still more ancient date. The present building is of many dates and many styles of architecture. The magnificent Norman doorway in the South porch, With its almost perfect array Of bibbet, beakhead. and zig-zag mouldings. is the oldest part of the. Church (c. 1150). Next to this in interest, but perhaps a century later, is the nave with its massive, semi-square columns, into which the chamfered. pointed arches fade curiously away without any true capitals. In the easternmost pier of this arcading is a small piscina. or stone sink, for carrying away the water used in cleansing the Communion vessels. This points to the existence formerly of an altar standing at what is now the Chancel arch. that must have been in regular use before the Chancel was built The chancel. with its beautiful columns of Dartmoor granite was added in the 14th century, a period when many Devon churches were enlarged and beautified under the direction of Bishop Grandison, of Exeter. At some time an oak chancel screen was put up, to separate the new chancel from the old nave, hut it was taken down by Daniel Evans, who came as curate to the church in 1813. It was this Daniel Evans who originated the Bible Christian movement in Shebbear. Baring Gould writes of him—”In 1815 a certain Evans, a Welshman, was curate at the church. Ile was a strong Calvinist. and removed the beautiful carved oak screen from the church, as a protest, against symbolical as distinguished from real worship.” It is thought that parts of the old screen were built into the pulpit, the reading desk, or the lectern. It was not until 1938 that this characteristic feature of the church was restored by the erection of a new chancel screen of rich carved English oak.

Below a low, obtuse arch in the wall of the South aisle is a tomb of alabaster with recumbent effigy of a female in a flowing robe, with pleated collar and ample widow’s veil. From her right wrist. hangs a rosary. Her’ head is supported by kneeling angels; her feet rest on a crouching hound. The figure (1350-1450) is traditionally said to represent the

Lady of Ladford. Risdon, the antiquarian, speaks of a “monument covered with pews, that of the Lady Prelidergist of Ladford and Beare. who built the South aisle and covered it with lead.”

In the sanctuary there is another piscina, and in the South porch a trefoil-headed holy water stoup, both of which have been “restored” almost beyond recognition. The tracery of all the windows is modern, with the sole exception of the 13th century lancet window in the North wall of the Church, adjoining the Tower arch, which may have the original stone work. The Chancel arch, too, is modern and a curious feature will be noticed in the inaccurate alignment of chancel with nave. This may be intentional, the builder’s attempt to represent the inclining head of the Saviour on the Cross. Or it may be accidental. Old Devon builders seem to have had a way of building without cither rod or staff, plumbline or level, just as the fancy took them.

Shebbear Church suffered the fate of many another in the wave of restoration fury that swept through mid-Victorian days. Mr. Bligh Bond concludes his description of the church— ” This church was renovated in the most atrocious manner in 1872 and utterly vulgarised.”

One of the treasures of the church is the Jacobean pulpit with its rare carvings of black oak, and rich. symbolic ornamentation. There is some interesting plate including an embossed silver sweetmeat dish (1659). a silver bleeding bowl (1671). both used patens for the Communion. The six church bells modern, the first and the sixth having been cast in 1863 the other in 1792. There is the usual story of their sweet tone being due to some silver having been thrown in at their casting, by the Lady of Ladford. at Shebbear. But look at the date of the and look at the date of the Lady of Ladford. Sweet tone of bells is more often due to the ringers, for which Shebbear has always had a name.

In 1911 the East end of the South aisle. Lady Prendergast’s aisle, was dedicated by the Bishop of Crediton as a Lady Chapel. Its East window is in memory of the Balkwill family. That in the South wall commemorates Lieut. Prior Ponsford, who gave his life in the first Great War. A tablet inscribed with the name of all Shebbear men who served in the Great War faces the main entrance of the church.

In 1938 a two-manual organ of oak, which had been put up in the Lady Chapel, preventing any use of the Chapel for worship, was removed to a new carved oak organ gallery in the West end of the church, the gift of the Lady of the Manor, and replacing one known to have been there in 1849. In 1939 there were further additions, a Lych gate at the entrance of the churchyard. and enrichments of the Lady Chapel.

The Church of Shebbear belonged originally to the Abbey of Torre. There is on record the admission of a clerk to “Sheftbert” on the presentation of the Abbot of Torre, in the reign of King John. For many years Sheepwash Was a chapelry of Shebbear, and Thomas Trevethan, who became Vicar in 1793 (Daniel Evans’ Vicar) had charge of Buckland Filleigh and Sheepwash. as well as of Shebbear. an early example of the amalgamation of parishes. There are few Churches in the Exeter diocese can show a longer succession of Vicars, dating back to 1203, when Alan de Hertiglie entered upon his office. Intriguing names among them are Peter Durlyng, 1285, and Jordan De Walcedoune, 1411, Sir George Luxton, 1556, and Halnetheus Arscotte, 1572. are examples of the way old names abide in country places.

Shebbear Church suffered, as did Buckland Filleigh, from the Cromwellian storms and the Civil War. Henry Wilson, Rector of Buckland, was turned out. and his place taken by -the Welsh Independent, Owen Williams. whose holding of the living is commemorated by the curious bronze inscription on the West wall of the Church Tower— “Mia Goda Gida.” In Shebbear the ejected Vicar was William Battishill. His was a stormy life. One is glad to know that he returned to his own again. A slate slab on the North wall of the sanctuary records that he died Vicar of the parish. in 1666, and was buried there.

The Church records date from 1576, and with one exception, they are complete. In one of the earliest registers is a written note—”No entries of Baptisms, Marriages or Burials from the year 1661 to 1668 to be found; the leaves containing the several entries of the intermediate years are supposed to have been designedly cut out from this place, or perhaps no Entry was ever made during that time”-signed D. Evans. Curate, May 20th, 1813. This is Bible Christian Evans’s first entry in the registers. In days before any civil registers were kept, the Church’s records would Often have to decide. questions of ownership or of rank. The seven years’ gap in the registers looks like dirty work somewhere, that is now beyond repair.

The Bible Christians and Shebbear College

To many people Shebbear’s chief claim to recognition lies in the fact that it was the birthplace of the Bible Christian movement. The story starts in the parish Church; its first scene is set under the village oak in the year 1813. In that year a man called Daniel Evans appointed curate of Shebbear. He was a man of evangelical zeal, unusual in the church of those days. and his very first sermon at the church aroused the deep interest of many. of none more than of Mr. and Mrs. John Thorne. of Lake Farm. who stayed on long after the service talking under the old oak with their friends of the strange things they had just heard.

Stirrings of revival were making themselves felt all over North Cornwall and North Devon at that time. William O’Bryan, a free lance evangelist, who had broken away from the Methodist connection. had become a real power in these depressed, neglected regions. He was a welcome preacher in many of the villages round about. but felt that there was no need for him to visit Shebbear where the Parish Church was showing itself so very much alive under the keen ministry of Daniel Evans. The result was that William O’Bryan. who was destined to play such a leading part in the creation of the Bible Christian movement, was a stranger to Shebbear until 1815, when. after preaching at Langtree. he accepted an urgent invitation from the Thornes to come over and see for himself the great things that were doing at Shebbear. Much talk no doubt was had. much thought, before it was decided to break away and form a new Society. But on October 9th, in the year of Waterloo, 22 persons (the Thorne family contributed seven of them Daniel Evans made an eighth), gave in their names to William O’Bryan at Lake Farm, the Bible Christians became a distinct and separate body, and the first page of long and most remarkable chapter in the history of Shebbear was turned. There seems to have been a tendency at first to call the members of the new Society. Bryanites. but gradually the name was changed to “Bible

Christians,” a name given them by the public, who noticed that members always carried their Bibles with them when they went to worship.

At the first Bible Christian Conference, August 17t, 1819 held at Baddash, Cornwall. the number of members had increased to nearly 3.000. One of the first chapels to be built by the new Society was Lake Chapel. Shebbear. part of which still stands. Young James Thorne. son of John and Mary, preached at the setting up of the corner stone in 1817, and O’Bryan at the opening of the building the following year. This chapel was given, and still displays the name “Ebenezer.”

In 1829. the Society had over 8.000 members, but. A set back about that time reduced numbers to 6,000, largely owing to the action of O’Bryan. who demanded almost dictatorial powers, which the members were unwilling to concede. In 1841 a new and significant move was made. Some of the most influential members felt that only by sound education could the full value of tole movement be developed and maintained. There was ready to hand small private school, Prospect House on the site of the present Shebbear College, carried on by Samuel Thorne and his wife. With this as a nucleus “The Bible Christian Proprietary Grammar School” was started. and for its first headmaster, the Rev. C. H. O’Donoghue, formerly Chaplain to King William IV was chosen. Unfortunately the new headmaster died, after only a few months work, and a very difficult time followed. The problems became so acute that Mr. and Mrs. James Thorne. who had retired to Bideford were to come back and keep things going. It was a grim struggle, against seemingly impossible odds, and not until 1864 did relief with the appointment of Thomas Ruddle, a young London man of rugged and forceful personality. Confidence was gradually restored, numbers begun to increase and candidates for the Bible Christian Ministry were also enrolled. We get a glimpse of Ruddle’s bluff, downright character, the extraordinary problems of task, and the isolated nature of the place, from a remark he made to the driver who brought him out from Bideford-“It seems to me that you would do well to sell some of these chapels and buy a few people.”

And now began a Herculean labour, the carrying on and development of the school for the boys of the Bible Christian people, and of the Pastors’ Training College, for the young men who wished to enter the B.C. ministry.

Either would have been enough for most men, but Thomas Ruddle found energy and capacity enough for both. The number of those preparing to ministers was small, seldom exceeding twelve. Their life at the College Was rough but disciplined; accommodation was limited and the men slept in the one large room, called familiarly “The Saints’ Rest.” Ruddle was little of a theologian. but he was a worker and in dead earnest, and most men reckoned that his presence and guidance were in themselves a liberal education. After events were to prove this.

In 1876 the school shed its unwieldy title, and took the name by which it was to known far and wide. Shebbear College. Thomas Ruddle was headmaster for 45 years, and he set once and for all the seal of his own rich personality upon the place. He was succeeded in 1909 by Rounsefell, whom Ruddle himself pronounced to be “one of the best preachers in Plymouth and the very best teacher.” Shebbear College has been as insistent most good on the three r’s of all sound education, but went one better than most when it started off with two such r’s as Ruddle and Rounsefell, who between them covered nearly 70 years of its early history.

With the scantiest of funds and material equipment the Bible Christian movement spread across the world before the end of the 19th century. On not a few of its missionaries is set the authentic seal of the apostolic age—” in weariness and painfulness. in journeyings oft….” From one of them comes a genuine flash of classic Christian utterance. the dying words of Samuel Thomas Thorne. In China—“Lord butter our lips; make us glib to preach Thy word and tell of Thy goodness,” words that for ever link Devon with dedication, grace with green pastures.

Reunion with the main Methodist body came before the Bible Christians could celebrate their centenary. What began in Shebbear, not ended but passed on, in London.

There at the City Road Chapel, Wesley’s old Chapel, on September 17th, 1907. the Bible Christians ceased their separate existence, and joined again the body from which they sprang. One thinks of Kingsley’s majestic. words about his beloved Torridge, Shebbear’s Torridge, how “Torridge joins her sister Taw. and both flow together towards the broad surges of the bar and the everlasting thunder of the long Atlantic swell.” One thinks of Shebbear Church, too. and of Daniel Evans under the old oak tree, preaching of the new life of the Spirit ” which all they that believe were to receive.” Daniel Evans planted, William O’Bryan watered, but it was God Who gave, as it is always God Who gives, the increase. We may yet see greater things than these, and the wheel run full circle to its rest.

Donald Davey

We are lucky enough to have this wonderful photograph of local Blacksmith Donald Davey. He worked from what is now Farriers, previously Anzac.

Gary Dixon marriage to Jane Geary

Last updated on 24 August 2025 by Admin